-

Posts

652 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Posts posted by Daniel

-

-

So, how deep could the water be and the ship still be able to anchor? And what's the limiting factor?

I think having a 100-fathom anchor cable doesn't let you anchor in 100 fathoms of water. I think that for the anchor to bite properly, the anchor cable needs to be at an acute angle to the sea floor, and pictures I've seen of ships at anchor show the ship several hundred yards away from being directly above their anchors. You would only go directly above your anchor when you were preparing to haul it up.

But is the length of your anchor cable the limiting factor? Beyond some length, does the combined weight of the anchor and cable become too much for the crew to lift up, or for the capstan to withstand?

-

While the ship is wearing (i.e. the stern of the ship is passing through the wind's eye as it turns), the boom of the spanker or other fore-and-aft sail may sweep across the deck, which can knock you overboard or break your neck if you're not looking out for it.

Also, the blocks/pulleys are always moving about in unpredictable directions aloft. Once, while I was on the foremast head of the St. Lawrence II, the crew on deck started lifting something with a block and tackle, and the block caught my shirt and started to lift me. They stopped and I was able to disentangle myself, but less alertness on their part could have thrown me off the mast head. While it is very unlikely that the captain or other senior officer would be aloft himself to save the hapless, his timely shouted warning could prevent such an accident.

-

Great pictures! I see that there was some sort of raft or platform used to avoid having to stand in the water while working on the bottom. But I didn't realize that it was not necessary to get the ship entirely out of the water before careening.

Thank you very much!

-

Careening: the act of beaching one's ship, turning it over on its side, cleaning the bottom and adding/replacing hull planks. WIthout careening, teredoes and barnacles and seaweed will first slow and then destroy the ship.

Now, even a small vessel will have a draught of five feet or more; the brigantine St. Lawrence II, for example, has an 8.5 foot draught. So as you sail your ship toward the beach, you will run aground in five to eight feet of water. Obviously,it will be difficult or impossible to work on the bottom while standing in the middle of crashing surf. In ordinary seas, the solution is presumably to ground the ship at high tide; when the tide goes out, your ship is left high and dry and ready to work on.

But the Caribbean Sea has no appreciable tides. How do you careen there? We know that pirates did careen in the Caribbean; Captain Lowther was captured while careening on Blanquilla, off Venezuela. Did the pirates somehow drag fifty- or sixty-ton sloops out of the water and onto the dry beach, and then back again? And what did they do with big ships like the Queen Anne's Revenge or the Royal Fortune?

-

Awesome! Thanks to both of you!

-

Thanks! Two followup questions. 1) How do you make sure the gun is not going to fire while you're working on it? 2) How long does it take an experienced person to do these things?

-

Rousted my son with pirate talk this morning, but didn't have much chance to talk like a pirate after that.

-

I love the part where he drinks the water off the leaf!

-

A simple question, I think: how, historically, did people draw the charge from a flintlock or other muzzle-loader if it misfired? If only the priming powder was wet or spoiled, re-priming would seem relatively easy, but if the actual main charge in the gun barrel proved to be wet or otherwise faulty, how did you get it and the ball and the wadding out?

In the novel Treasure Island, Stevenson has Jim Hawkins draw the charge on one of his pistols and then reload it in the time it takes Israel Hands to climb to the Hispaniola's mizzen top. That sounds impossible; is it?

-

TREASURE ISLAND (1990)

Featuring: Christian Bale, Charlton Heston, Oliver Reed, Julian Glover, Richard Johnson, Clive Wood, Christopher Lee, Michael Halsey, Pete Postlethwaite, Nicholas Amer, Isla Blair, John Benfield, John Abbott, James Cosmo.

Daniel’s rating: 4½ out of 5.

Synopsis: Billy Bones is an unwelcome lodger at Jim Hawkins’s Admiral Benbow Inn; Bones’s ex-comrades, pirates all, are even less welcome when they come looking for his treasure map. Young Jim escapes with the map, and together with his grown-up patrons Squire Trelawney and Dr. Livesey, they sail in search of the treasure. And with them sails Long John Silver, the warm and fatherly one-legged sea cook who just happens to be the smartest and most ruthless of the pirates who buried the treasure in the first place. But Jim accidentally learns that Silver plans to lead a mutiny, take the treasure, and kill Livesey, Trelawney, the captain, and perhaps Jim too.

Evaluation: I’ve seen eight versions of Treasure Island in my life, and this one by Charlton Heston’s son, Fraser Clarke Heston, is the best. Not because it’s the truest to the original novel – although it is – but because it has the clearest vision and purpose. Both when Heston is telling Stevenson’s story and when he is telling his own, he takes the tale seriously, and lavishes love on it.

Let’s start with the elder Heston. No production of Treasure Island can be better than its Long John Silver, and Charlton Heston is one of the best ever to play the role. His performance here is dialed back several notches from Robert Newton’s full-broadside dynamism; this Silver is quieter and more restrained, but has every bit of the cunning and subtlety of Stevenson’s original, all covering up a satanic savagery at his core that he lets loose when it serves him best. But he has another side, a paternal side that admires Jim Hawkins’s wit and pluck, which is so much like his own and so unlike his stupid and weak shipmates’. He clearly means it when he tells his pirates, “I like that boy. I’ve never seen a better boy than that. He’s more a man than any pair of you bilge rats aboard of here!”

The other half of the story is Christian Bale's Jim Hawkins, struggling to live up to the example of his heroes: Livesey, Trelawney, and Captain Smollett. This is why we are supposed to root for Jim's allies to find the treasure first, even though they have no more lawful claim to it than Silver’s pirates do: because they are morally superior to the pirates by dint of their honesty, piety, courage, loyalty, temperance, and industry. These values sound stuffily middle class to us today, but they were the steel and concrete that built Stevenson’s world. Jim aspires to these virtues, and by the end of the movie he has won them. Jim stands by his word to Long John Silver to testify in his favor in court, but when Silver gruesomely describes his own imminent hanging in an effort to get Jim to go beyond his word and let SIlver loose, Jim won’t bite the hook. His acid reply, “Maybe you should have thought of that before you turned to piracy,” seems to be aimed not only at Silver, but at the sappy ending of the 1934 Wallace Beery version.

Behind the leads is a standout supporting crew, led by Julian Glover’s Dr. Livesey, who slowly realizes that his deference to Trelawney is misplaced, and grows into the leader of the expedition. Then there is Oliver Reed, surely the best Billy Bones ever. The movie retreats a little from its moralistic stance to show what a tragic character Bones is; he beat the odds for twenty years, evading scurvy, the noose, cannon fire, malaria,yellow fever, storms, and shoals, to finally reached the pirate’s dream of retiring with his plunder. And having achieved everything he ever wanted, he literally cannot think of anything to do but to drink himself to death. The pathos is still greater when you consider that Reed himself had a serious drinking problem that finally killed him.

As I said, this is a very faithful adaptation, probably the closest ever made to Stevenson’s original. But the movie’s real virtue is not slavish copying for its own sake, but simply recognizing what was best in Stevenson’s original and using it to best advantage. When Fraser Heston departs from Stevenson’s text, it is almost always to make an improvement. Stevenson makes Jim’s mother faint, even though she is a hardy and determined woman; in the movie, she defends her inn at gunpoint, making her a far more memorable and consistent character. Stevenson makes Israel Hands a coxswain, which never plays any role in the plot; in the film he is a gunner, which proves very important. Stevenson’s Silver makes an uncharacteristic tactical error by assaulting the stockade without any support or plan; here, he has a cannon dragged up to soften up the stockade, which incidentally lets him fight in the battle personally, and which very nearly defeats the good guys. But one deviation from the book is less justifiable: it makes no sense for Billy Bones to admit his real name as soon as he walks in the door of the Admiral Benbow, since his whole reason for staying there is to avoid being recognized.

The film was shot on location in Jamaica and England, and has magnificent scenery, brought even more to life by the Chieftains’ stirring musical score. Long stretches of Stevenson’s beautifully salty dialogue are adopted intact, making you feel that you are really in the 18th century. And the battle scenes, apparently done without a fight choreographer, are outstanding, full of real desperation; at the end of the stockade battle, all the heroes are nearing exhaustion and gasping for water.

Not many directors are willing to suppress their vanity and tell another man’s story as best they know how. Fraser Clarke Heston was one of the rare exceptions. And that’s why this film is not only the best Treasure Island ever made, but a serious candidate for the best pirate movie of all.

Piratical tropes and comments: Like any version of Treasure Island, this one is heavy on famous tropes. Silver’s parrot Captain Flint is present, played by a red-lored Amazon that fits comfortably on the shoulder; she’s green, just like in the novel. Of course, there is also a one-legged pirate, although the movie follows the novel in giving Silver a crutch rather than a peg leg. And as always, there is the treasure map with X marking the spot – multiple X’s, in fact, since Captain Flint decided not to put all his eggs in one basket.

“I’m cap’n here, by ‘lection,” says Silver, quoting the book and accurately showing how pirate captains were chosen. Although we never see the articles of Flint’s crew, it is clear that they have them and that they lay great store by them; Silver himself is not ready to break the “rules” until pushed to the last extremity. But it is clear that these rules are a way the pirates have of getting along in company; they are not moral principles, and the pirates discard them quickly whenever they are left alone, or even in pairs, as Billy Bones and Israel Hands show.

The knife in the teeth is present here, and makes some sense in context. Israel Hands is trying to stab Jim Hawkins; when Jim climbs the rigging, Hands just clamps the blade in his teeth and climbs after him, rather than lose time by tucking the blade back into the secret scabbard inside his shirt where he had it hidden.

As usual, the Hispaniola is portrayed by a full-rigged ship: the same Bounty that appeared in the Marlon Brando Mutiny on the Bounty and the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, and which was tragically lost in Hurricane Sandy along with her captain and a deck hand. It is the only pirate ship I’ve seen that has a pump, which Jim Hawkins improbably uses as a weapon. The ship is equipped with a spritsail and spritsail topsail, which would have been some of the last of their kind in the 1750s, but it does have a wheel, which by that time had been widely adopted. The sails are recognizably 19th century – short-leeched, taut, and tapering toward the top – instead of the long-leeched, billowing sails of the early-to-mid- 18th century. But the Bounty was a beauty and Fraser Heston knew it, giving the ship a full share of the spotlight.

This is the only pirate movie I’ve ever seen which uses the word “avast” correctly, as a command to stop what one is doing, as in Smollett’s crisp order “avast talking.” Other nautical language is sprinkled liberally throughout, and used very accurately: “to raise an island” meaning to come within sight of it, “a lee shore” for a dangerous situation, and “ran down our easting” for making eastward progress. But Silver’s use of “bucko” as a term of endearment is a late 19th century anachronism.

The usual cocked hats, broad belts, and puffy-sleeved linen shirts are on display, but no bucket boots. Trelawney and Livesey have short white wigs that look like something George Washington would wear. Several of the sailors wear peaked hats that could almost pass for Monmouth caps, except that they bend backward instead of forward.

The Jolly Roger here appears in its most popular form: white full-face skull above crossed bones on black field. The movie faithfully copies Stevenson’s rather absurd use of the flag, even including Ben Gunn’s silly observation that “Silver would fly the Jolly Roger” above the stockade if he had captured it! Kudos, though, for showing a merchant ship flying a Red Ensign rather than the full Union Jack.

Weaponry is ordinary flintlocks and basket-hilted cutlasses, which look fairly authentic except for being a bit on the long side. Jim is put through the harrowing ordeal of having to re-prime his pistols while Israel Hands climbs up the rigging to murder him. We get to see a blunderbuss, rarely shown in the movies, but it is used by Jim’s mother, not by the pirates. Its kick is enough to knock her down!

In all, there’s plenty of piratey goodness to go around. Certainly, there’s more than enough for a story which (we too easily forget) takes place a good twenty or thirty years after the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Charlton Heston's Long John Silver.God, how I love being evil!Christian Bale's Jim Hawkins really needsa Bat-Signal about now.Oliver Reed's Billy Bones, lookingfor trouble - and finding it.Julian Glover's Dr. Livesey isimpressed by Jim Hawkins.Michael Halsey's mild, inoffensive Israel Hands.Introducing the Bounty in the role of the Hispaniola.Israel Hands brings a knife to a gunfight.Ben Gunn has to stop meetingLong John Silver like this. -

In his book Never Cry Wolf,Farley Mowat claimed to have taken this to an extreme. He imitated the wolves he was watching by sleeping in five-to-ten minute increments, at which time he got up, turned around, and went to sleep again. He said that this was "infinitely more refreshing than the unconscious coma of seven to eight hours' duration which represents the human answer to the need for rest." Bear in mind, though, that it remains controversial how much of Mowat's book was fictional and how much true.

-

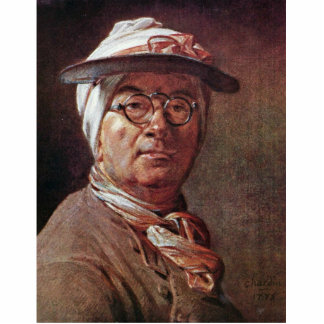

Chardin painted two self-portraits showing himself with glasses - one with sides, and one without!

Chardin, Self-Portrait, 1771.

Chardin, Self-Portrait, 1775.

-

Coastie's thread on the Astrid started me thinking about how ships were salvaged back in GAoP. Like many landlubbers, I tend to think of a "lost" ship as sitting on the bottom of the sea without a trace remaining, forgetting that ships, like the Astrid, can be sitting on the rocks with not only their masts but substantial parts of their hulls above water. Such a ship might not be out of reach of 18th century recovery technology. We hear frequently of wrecker-pirates, who swarm out onto a wreck and strip her, or even lure a ship onto the rocks with false lights; how did they go about getting the loot?

The one contemporary source I know of about 18th century salvage is Johnson's passage about the 1715 Spanish plate fleet.

It was about two Years before, that the Spanish Galleons, or Plate Fleet, had been caſt away in the Gulf of Florida; and several Veſſels from the Havana, were at work, with diving Engines, to fiſh up the Silver that was on board the Galleons.

The Spaniards had recovered ſome Millions of Pieces of Eight, and had carried it all to the Havana; but they had at preſent about 350000 Pieces of Eight in Silver, then upon the Spot, and were daily taking up more. . . . the Money before ſpoken of, was left on Shore, depoſited in a Store-Houſe, under the Government of two Commissaries, and a Guard of about 60 soldiers.

So, they had "diving engines." What kind of engines might those be? Was this work for slaves, or free men? What could be salvaged besides coin? Are these wrecks partly showing above water, or completely submerged? Etc.

-

Looking at that last article, it sounds to me like the reporter didn't understand that "salvage" could also mean "turn over to the insurer for scrap value" as well as "sail again."

Thanks for keeping us posted!

-

PIRATES (1986)

Directed by Roman Polanski

Featuring: Walter Matthau, Cris Campion, Damien Thomas, Charlotte Lewis, Olu Jacobs, Ferdy Mayne, David Kelly, Richard Pearson,

Daniel’s rating: 2 out of 5.

Synopsis: One-legged Captain Red and his crewmate Jean-Baptiste begin the movie lost on a raft at sea. They sight the Spanish galleon Neptune and manage to climb aboard, where Captain Red’s stupidity immediately gets them chained in the brig. While imprisoned, Red learns that the Neptune carries an Aztec throne of solid gold. Plotting to seize the treasure, he leads a mutiny, which fails, and he is sentenced to hang along with Jean-Baptiste, but he still has more tricks up his sleeve.

Evaluation: When I first watched Pirates about 12 years ago, I loathed it. And having revisited now . . . well, I loathe it less this time, probably because my expectations were lowered to zero, but I still don’t like it. The main reason is that I don’t think Polanski ever figured out what kind of movie he wanted Pirates to be – an Indiana Jones-type picaresque adventure, or a black comedy like Brazil. He then tried both and accomplished neither.

The movie is already off course in the opening scene, in which Polanski proves that he doesn’t understand what makes pirates so powerfully magnetic: their appeal to our inborn tribalism. We humans evolved as tiny groups of hunter-gatherers, relying for our lives every second of the day on our fellows inside the tribal circle, and permanently at war with every other human being beyond the limit of that circle. Pirate crews were the last gasp of that way of life. As Bartholomew Roberts’ articles say, he who cheats the company to the value of a dollar is marooned – only people outside the company are fair game. Captain Red openly betrays this ethic in the first five minutes of the film, robbing his crewmate Jean-Baptiste of the tiny fish he caught, then trying – twice – to kill and eat him.

OK, so Red’s not much of a pirate when he’s hungry and dehydrated, but what about in happier times? Well, no, he’s not any better with a full stomach and refurbished peg leg. Where Long John Silver is smart, and only fails because he has to rely on his foolish fellow pirates, Red is usually stupid, with intermittent flashes of low cunning, and his fellow pirates are undone by relying on him. When his stolen ship is stolen back from him, he tries to recapture it by leading a flotilla of boats right into the galleon’s broadside, with predictably disastrous results. His plan to capture the Aztec throne at Maracaibo goes awry, twice, through his own bungling, with his crewmates bailing him out each time.

Still more frustrating is that Red’s crewmate and co-star, Jean-Baptiste, never comes into his own. At the beginning of the film, he accepts all of Red’s abuse without a murmur. Red can’t even be bothered to say his name, calling him Froggy throughout the film. Then Jean-Baptiste falls in love with Dolores, the beautiful niece of the governor of Maracaibo – and this changes him not at all. At the end of the movie, he is still doing everything Red tells him to, even when this could have

and does

cost him the woman he loves. This pattern is repeated in Red’s ally Boomako.

Boomako succumbs to a particularly cruel instance of the Black Dude Dies First trope. He is shot dead within arm’s length of both Red and Jean-Baptiste, neither of whom so much as glances at the man who tilted the Neptune’s crew in favor of making Red captain, gave Red and Jean-Baptiste the treasure, and saved both their lives.

Floundering from its weak characters, Pirates is then sunk by one more shot: the horrible cinematography. The focus is often dull, the light usually weak and browning out the images, or else so strong that it washes everything out. The best way to say it is that when I watched The Black Pirate, I saw an image I wanted for the review every five minutes, and ultimately I had far more images than I could use. I never once saw an image I wanted while watching Polanski’s Pirates. This is supposed to be the Caribbean and was actually shot in the Mediterranean; is it really too much to ask that it look beautiful?

This is, of course, more than enough to ruin the movie, but it has some virtues that I didn’t notice the first time around. John Brownjohn wrote some quite good lines for Captain Red, making him sound very salty but still intelligible, with phrases like “Do you see the course I lay?” for “Do you see what I mean?” I have always loved Walter Matthau, and he manages to give his repulsive character a little superficial charm. And I had forgotten how heart-achingly beautiful Charlotte Lewis was, although it’s unfortunate that her character, Dolores, is given almost no chance to develop. Damien Thomas makes quite a pleasingly nasty villain as Don Alfonso, his performance even more remarkable for being a last-minute replacement after Timothy Dalton walked out. Ferdy Mayne’s brief but shining turn as the murdered Captain Linares seems almost to channel Christopher Lee. A lively score by Philippe Sarde gives the movie some much-needed spunk. A number of the period details are good too, but more about that later.

Two scenes are key to understanding Pirates: one when the Neptune’s mutineers jump meekly back to work at Don Alfonso’s command, and the other when Red’s old pirate crew stands gazing dumbly at him until they’re sure he’s really back. Incompetent and untrustworthy as Red is, nobody has any initiative without him; ordinary people are cowed and spiritless until he takes charge. This is supposed to explain, and even justify, the way his own associates continue to treat him well even after he abuses their trust. It’s not surprising that the man who directed this movie is a convicted pedophile.

Piratical tropes and comments

Pirates is set in 1660, give or take a year, after the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659 but before the death of Cardinal Mazarin in 1661. The props are mostly appropriate for that period, with broad-brimmed hats for Captain Red and the aristocratic Spaniards; the Spanish dons are also shown continuing to be attached to old-fashioned rapiers while the rest of Europe was moving on.

The Neptune is a pretty amazing prop. She’s called a “galleon,” but she looks more like an East Indiaman to me, with a double row of cannon and that high, sloping sterncastle that you see on the Batavia. The beakhead, though, looks like something from the late 17th or early 18th century: short and upswept instead of long and low like the galleons and early Indiamen had. But for all that, she’s huge, she creaks, she has a magnificent set of stern lanterns, and she’s beautiful. The low headroom of period ships is accurately shown: one mutineer puts it to good use by repeatedly slamming his opponent’s head into the ceiling. The Neptune has rats, and the sailors are correctly shown holystoning the deck. The Neptune is still docked in Genoa today, a graceful monument to a bad movie.

Hardly any cutlasses appear in the movie; the Spanish use cup-hilt rapiers, while Matthau uses a shell-guard rapier; I never saw him actually use the cutlass that he's shown holding in the movie poster. But the movie also showcases two real pirate weapons that rarely get any play on screen: the boarding axe, which Boomako uses with deadly effect in the mutiny, and grenades, which Red’s pirates throw into the gunports and hatches while assaulting the Neptune.

The Jolly Roger here is the famous Rackham version – a skull above crossed swords – later used in both Cutthroat Island and POTC. It is, of course, forty years too early for that or any black Jolly Roger to be used. Red apparently carries a full-sized Roger in his pocket, which he pulls out and gives to Jean-Baptiste when they capture the Neptune. Much like Stevenson in Treasure Island, Polanski doesn’t know what the flag is used for; his pirates fly it even when not chasing a prize.

A ghastly period-correct touch is used here: Spain's main method of capital punishment in the colonies was the garrote, not the gallows, from at least the time when the Inca emperor Atahualpa was executed.. We are shown the aftermath of a mass garroting in gruesome close-up, which utterly destroys any attempt that Pirates was making at comedy.

Much as in the 1999 Treasure Island, we are treated to the painful side of period medicine. Captain Linares is given an enema with a gigantic syringe that looks like something right out of Mission’s kit.

Captain Red is a virtual walking pirate lexicon, using “alongside” for “beside,” “my hearties,” and so on. He’s also the only movie pirate I’ve ever heard mention “the Brethren of the Coast,” although no other captains of the Brethren play any role in the movie at all.

The major pirate accoutrements here are Red’s peg leg and Jean-Baptiste’s earring. The peg leg proves a constant bother to Red, as he’s always getting it stuck and at one point has to pay a carpenter to cut him a new one.

The games pirates played with prisoners included forcing them to ride each other around the deck. Pirates takes this one step further, as the pirates force their captives to play “Dead Man’s Nag,” where Don Alfonso and his men are forced to sword fight each other to the death while riding on the shoulders of other captives. Alfonso does as bidden and stabs his fellow hidalgo, proving that when his life’s on the line, he'll kill his friends just as readily as Red will.

Walter Matthau as Captain Red;there's less to him than meets the eye.Cris Campion as Jean-Baptiste; it would have beenbetter if he'd turned this face toward Red more often.Damien Thomas as Don Alfonso. "I'm a Spanishdon; what do you mean I'm not the good guy?"Charlotte Lewis as Dolores, trying tomitigate Don Alfonso's nastiness.Olu Jacobs as Boomako: overworkedand underappreciated.Open boats versus galleon's broadside..

This does not end well.

-

What happens if Astrid can't be refloated? Will she simply be left there indefinitely? Doesn't she pose a navigation hazard?

-

Cool. That explains a lot, like why English sailors are often portrayed clean shaven in period sources. Although some pictures show sailors so young they might not need to shave yet.

A crown, I think, was 5 shillings, so if each sailor paid half a crown, that would be two and a half shillings, or 30 pence - the value of five shaves on land. Not bad for a voyage that might last a year or more!

-

There are many good threads like this about shaving, but I don't see anything about shaving cream. Was it used in period, and if so, where did they get it? Wikipedia's article on shaving cream says that hard shaving soap was used before 20th century shaving creams, but it only dates that back to the beginning of the 19th century. The last mention of that was shaving cream in ancient Sumer, 3,000 B.C., which was made of wood alkali and animal fat. Was shaving soap already around in GAoP? And how do you use it? Mix it with water in a shaving basin and then brush on?

Other threads seem to suggest that most men didn't shave themselves, but went to a barber once or twice a week. That's sixpence a pop, according to Elena's source from Foot Guards, so a seaman who shaved once or twice a week would end up spending from 26 to 52 shillings a year on shaving. An ordinary seaman only earns 228 shillings a year, so that's somewhere between 11 and 22 percent of your annual salary going to shaving. This makes me wonder if shaving might be something of a luxury of the middle class in our period.

-

THE BLACK PIRATE (1926)

Directed by Albert Parker

Featuring: Douglas Fairbanks, Billie Dove, Sam de Grasse, Donald Crisp, Anders Randolf, Charles Belcher, Tempe Pigott, Charles Stevens, John Wallace, Fred Becker, E.J. Ratcliffe.

Daniel’s rating: 3½ out of 5.

Synopsis: A Pirate Crew robs a merchant ship and blows it to Kingdom Come, together with all the passengers and crew. An old man and his son are the only survivors . . . whoops, make that the son is the only survivor. The newly orphaned son (Fairbanks) swears revenge against the Pirate Crew, which just happens to be burying the treasure on the same island that he washed up on. Calling himself the Black Pirate, he joins the marooners, offering to prove himself by single-handedly capturing the next ship they meet. He makes good on this boast, but the prize ship carries a Princess who is just too pretty for the Black Pirate to allow her to be blasted to bits.

Evaluation: The Black Pirate is a lot like Pirates of the Caribbean. Both are totally absurd, and both are so much fun I don't care how absurd they are.

It's easy enough to say why The Black Pirate is absurd. To start with, nobody EVER speaks to anybody else by name. In fact, only one character even has a name, which we learn when he signs a ransom note. (Read that again: he signs a ransom note). Then, even though every merchant ship in the movie is carrying either a Princess or a Duke, none of them bothers posting a full watch topside, sailing in convoy, or mounting enough cannon to fight off a not-particularly-well-armed pirate ship. Then, there are the battle tactics: once you’ve dismasted the enemy ship (with a single shot, no less!) and have it at your mercy, the next step is to scuttle your own vessel and mount a boarding attack by swimming. Then, all the governors’ soldiers wear skimpy black leather outfits that many a gay biker would pay good money for. Then, the pirates tell time aboard their ship with a sundial, which can’t possibly work unless the sea is perfectly calm and the ship never turns. Then, a pirate standing four feet behind Fairbanks fails to notice that Fairbanks’ hands are no longer tied. Then . . . but you get the idea.It’s harder to say why The Black Pirate is so much fun anyway. I think it’s because the film is so energetic. The whole movie only lasts about 95 minutes; the synopsis above covers only the first forty minutes. Everything comes at you at such a breakneck pace that you really don’t have time while you’re watching to kvetch about how implausible the thing that just happened was, because the next implausible thing is already under way. A lot of this energy comes from Douglas Fairbanks, who handles all his action sequences with such verve and gusto that he wins the loyalty of both the pirates and the audience effortlessly, although he may not even be a good guy at heart.

The other secret to The Black Pirate’s appeal is its visual flair. Some of the images seem inspired by Howard Pyle, especially Fairbanks marooned on the island after his father dies. The early Technicolor looks strange, but the flamboyant costumes and theatrical, silent acting are hypnotic. The movie is also very funny at times, especially when we learn that counting the paces on a treasure map is very tricky when you have a peg leg, and that sleepy pirates have interesting ways of keeping themselves awake.

So far, so POTCesque, but the cruel, flinty core of Parker’s The Black Pirate is absent from Johhny Depp’s and Gore Verbinski’s film. All the best pirate films are ambivalent toward piracy, never quite certain whether pirates are good guys or bad. This ambivalence appears in The Black Pirate too, as the hero commits some acts of brazen piracy to prove himself and some of the pirates protect him and the Princess. But overall, the movie leans decisively toward making pirates villains. The opening scenes show the freebooters dispassionately stripping rings and wealth from the men they’ve just murdered, and twice they sink ships with the intent to kill every man and woman aboard. In a modern movie, a hero would probably have swung in to rescue the doomed victims of the pirates at the last second, but that doesn’t happen here; scores of people are drowned basically to make the point that these pirates are really evil. In the most unsettling scene in the movie, the Pirate Lieutenant is sitting by the prisoners of the latest capture, when he suddenly sticks his sword into one of them, for no apparent reason but sheer boredom, and then looks at his red-stained sword in a vaguely irritated way, as if he hadn’t considered the inconvenience of cleaning his blade until now. The utter casualness of the murder is emphasized by not showing the dead man on screen. To the viewer’s eyes, just as to the murderer’s conscience, the victim doesn’t even exist.

In sum, The Black Pirate is a fantasy, although a darker-shaded fantasy than Pirates of the Caribbean. Like its great-granddaughter, The Black Pirate has nothing to do with actual historical piracy, and everything to do with the fancies that pirate art and literature put into our heads: sails billowing, trade winds in your hair, flashing blades, booming flintlocks, danger, action, excitement and romance, and all the other images that run through the head of a boy dozing on the schoolbus headed for home, or a girl at the end of a too-long study session in the library, or, for aught I know, a young foretopman at the masthead in the last few minutes before eight bells.

Piratical tropes and comments: Ladies and gentlemen, we have sighted bucket boots in 1926! I don’t know if this is their earliest appearance, but it is surely the most ridiculous. We first see them when Fairbanks has washed up on the island with his father, which means Fairbanks must have swum more than a mile while wearing them.

Like POTC, The Black Pirate doesn’t seem committed to any particular time period. Elizabethan props are most common, as the merchant ships are genuine galleons with those enormous foc’sles and sterncastles that you see in 16th-century illustrations. The Black Pirate also wears an Elizabethan cup-hilt rapier at one point, and both he and the Pirate Leader fight in Elizabethan style with rapier and main gauche. But the film also features walking the plank, which occurred in the 19th century when it happened at all, and the pistols are small true flintlocks with sharply curved butts, not Elizabethan wheel-locks and snaphaunces. Add to that the Georgian-era cocked hats, and Douglas Fairbanks’ short shorts, and sleeveless tunic, and you have a medley of anachronism.

Maybe the most unique trope that The Black Pirate established was using a knife to slide down the face of a sail, tearing the sail as you go. In the context of the movie, it makes some sense; Fairbanks does this very dangerous stunt not because he’s in a hurry to get down, but because he wants to disable the ship quickly. I can’t say for sure that this is the first appearance of the trope in fiction, but it is surely the one that made it famous.

The Black Pirate is unusual in that the pirates’ vessel isn’t a full-rigged three masted ship. It’s a single-masted craft with low freeboard and a giant black lateen sail, looking something like a tartan or a felucca. It’s an intimidating, evil-looking vessel, very well chosen, and it makes sense that it would be able to overtake the wallowing galleons. It does not have any visible gunports, though; the cannons are all tiny things on small carriages, and at one point a loose cannon is shown on deck while the pirates feast, which would be unbelievably negligent.

The Jolly Roger, in its incarnation as a skull with crossed bones below it, appears here. Everywhere. It’s in a flag flying from the rigging (not from a flagstaff or the masthead, curiously). It’s also on the pirate leader’s hat. Several of the pirates even have it tattooed on their chests, thus giving us another famous trope, the tattooed pirate.

The pirate leader uses another well-known trope, the knife clutched in his teeth. He has no reason at all to be doing this; he’s not fighting or climbing the rigging, he’s just counting the loot, and acts like “I’ll just bite my knife today, because I’m that cool.”

There are no parrots in sight, but there is a monkey, a cute little thing captured from the same vessel that the Black Pirate rode on. The pirates draw lots for the monkey, one wins, and the animal then disappears from the movie, never to be heard from again. Hopefully it did not end up like the monkeys that Bartholomew Sharp’s men found and ate in 1681.

The hidden-treasure trove is here, of course, although the pirates don’t bury the loot in a hole, instead carrying it into a hidden cave with a flooded entrance, another device that POTC would copy. Incidentally, the treasure chest is quite small, accurately showing that you could carry a fortune in gold in a very small space.

A pirate here is shown sporting a peg leg, which doesn’t fit very well, but eyepatches are absent. One pirate is missing an arm, but he just ties his sleeve over his stump, with no hook.

The piratical language used includes “Dead men tell no tales,” as well as “avast,” and “yo ho,” which are both incorrectly used as a vague way to say “hey!” But the usual pirate forms of address – “my hearties, matey, mates, bucko” – are absent. Instead the pirates call each other “bullies.” “Bully” was an often used word at sea; much like “bucko,” it was an unfriendly word for an overbearing, aggressive officer (i.e. “Bully Bob Waterman,” captain of the Challenge), but could also be a term of respect and even endearment.

Fairbanks wears earrings in both ears. This, combined with his short shorts, revealing tunic, mustache and armbands, makes him look very much a gay leather idol, or at least my conception of one. I assume this wasn't intentional, since Fairbanks does woo and win Billie Dove, but the effect is there. Back in the bad old days, when most gays had to live in the closet, I’m told they identified each other as “Friends of Dorothy,” a reference to Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz, so they could talk about each other without the intolerant community catching on. Having seen this movie, I really don’t understand why they didn’t call each other “Friends of Doug.”

-

Netflix also has Treasure Planet and Raiders of the Seven Seas on streaming.

-

Daniel, have ye seen the 1998 Frenchman's Creek (Tara Fitzgerald and Anthony Delon) to compare it with the 1944 version?

I haven't seen it; I will watch it and post a review in the coming months, if I can get the DVD.

-

I would like to be able to put text and images next to each other, with text on the left side and images on the right side of the screen when I post my pirate movie reviews. It would look so much better to have the images next to the words instead of being trailed at the end of the review like I'm doing now. But I can't seem to make the BBCode do that. I Googled a few tricks for doing this, but I can't make them work. The post editor apparently doesn't understand [imgalign=right] or [floatright], for example, if those codes are even able to do what I'm trying to do.

Is it even possible to put text and pictures next to each other on this board, and if so, how?

-

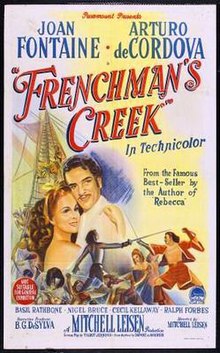

FRENCHMAN'S CREEK (1944)

Directed by Mitchell Leisen.

Featuring: Joan Fontaine, Arturo de Córdova, Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Cecil Kellaway, Ralph Forbes, Harold Maresch, Billy Daniel, Moyna MacGill, Patricia Barker, and David James.

Daniels rating: 3½ out of 5.

Synopsis: In 1668, wealthy Dona St. Columb dumps her oafish husband, taking her children from London to the seaside estate of Navron in Cornwall. There she meets Captain Aubrey, a French pirate who has been raiding the countryside from a ship anchored in a nearby river mouth, and sleeping in Navrons master bedroom, where he has fallen in love with her portrait on the wall. Dona is taken with Aubrey and joins him on his adventures, returning between times to Navron, her children, and her place as a lady. But how long can she keep her double life from being discovered?

Evaluation: Frenchmans Creek is based on a novel by Daphne du Maurier, author of Rebecca, which became one of Alfred Hitchocks best and most famous movies. Looking at this movie alongside Rebecca, I feel pretty safe saying that du Maurier was obsessed with elegant, lonely manors with seacoast views and names like Manderley and Navron.

I enjoyed Frenchmans Creek a lot more than I expected to. I was anticipating a limp, lifeless heroine bemoaning her fate in sterile black-and-white for a couple of hours. What I got was Joan Fontaine mmmm, Joan Fontaine lighting up the screen with verbal fireworks and, when necessary, kicking large quantities of butt. Fontaine nearly carries the movie all by herself. Her face is always full of intelligence and perception, accurately sizing up every character she meets, and she shows a palpable sense of excitement and love for adventure. Handed the worst, most stilted script youd ever want to crumple up and throw in the trash, she tosses off her lines effortlessly and naturally, making them sound almost like something an actual human being would say. But there's nothing she can do to save the film's ending, which simply ignores the most obvious solution to her problem.

Unfortunately, Fontaines leading man is not a good match for her. Arturo de Córdovas Captain Aubrey has dashing good looks, but no style; all he can express is puppy-dog enthusiasm, and he stubs his toe on every third word of that same awful dialogue that Fontaine handles with such aplomb. Córdovas weaknesses hurt all the more because Captain Aubrey is hard to believe to start with. I mean, why does a French pirate leave his ship anchored for days in an English river mouth and cavort in the locals beds instead of striking fast and hard and then escaping out to sea or back to France? Couldnt you easily get captured that way? Oh, wait, he does get captured that way, almost as if the plot demanded it. Aubrey says that A slipshod pirate is a dead pirate, and serves him right. Sorry, Captain, but that means you.

But Fontaine does get to face off with a nice, strong villain in Basil Rathbone. Rathbone is one of the greatest baddies of all time (pirate movie fans will remember him as Levasseur in Captain Blood), and here he's at his smarmy, sneering best as Lord Rockingham, the two-faced friend of Dona's husband Harry, his Captain Hook nose and steely baritone English accent full of menace. Best of all, Dona gets to defeat him herself, in a white-knuckle contest where both sides are playing for keeps.

The supporting cast is a pleasant surprise too. Cecil Kellaway steals scene after scene as Dona's sly, beneficent servant William, while Nigel Bruce delivers his patented stuffed-shirt performance as Lord Godolphin. Ralph Forbes as Dona's husband Harry evokes sympathy; while a modern movie would surely have caricatured him as a wife-beating monster, here he appears as a well-meaning bumbler.

Oh, and that sterile black-and-white photography I was expecting? Nowhere to be found. Frenchman's Creek is shot by George Barnes in rich Technicolor, with gorgeous sets everywhere you look. Two beautiful tall ships appear in the movie - Aubrey's flagship and his prize - and the mansion of Navron dominates the screen with stately splendor. The shots of the Cornish coast are breathtaking, taken in Mendocino County, California according to some reports. The only flaw in the production values is the saccharine score; Victor Young presents a butchered version of Debussy's Claire de Lune, which wouldn't have been any good for this movie even if it hadn't been mangled first.

Despite the weak dialogue and lame leading man, I doubt Frenchman's Creek could have been made so well today. The strong female lead who revolts against the role of wife and mother, so politically correct today, was very politically incorrect in 1944, and I think that made the movie better. If Frenchman's Creek were made now, Dona would probably act entitled to independence, not so much rebelling against her social role as unaware of it. Here, Dona is very conscious of the impropriety of her affair with Aubrey; she doesnt expect agreement or support from anyone for what she does, and, most importantly, she isnt sure whether she herself approves of what she's doing. In fact, Frenchman's Creek was remade for TV in 1998, and will be reviewed here in due course.

Piratical tropes and comments: Frenchman's Creek is pretty low on the trope-meter; there are no hooks, eyepatches, peg legs, parrots, monkeys, or even earrings on display here. There are lots of Restoration wigs, coats, and boots, but mostly on Restoration gentry, not on pirates. Captain Aubrey comes on set in a bizarre costume calculated more for a romance novel cover than for real pirating: it's a sort of a loose steel gorget and an open coat that shows off his bare chest. A number of pirates wear headkerchiefs, notably including Dona herself, while others wear round brimmed caps.

The swords here are all whip-thin transition rapiers, no cutlasses in sight. The swordplay has a prosaically realistic sound, more clicking than ringing, which is correct. But the deaths are absurd; everybody who's stabbed sort of freezes up and sinks down in absolute silence, while the guys who stab them hold the lunging pose to let us know that, hey, they've stabbed someone, instead of recovering instantly to the en garde position to avoid being counter-stabbed by their wounded opponents. The guns are regular flintlocks. At one point, the pirates assault a ship by swimming, holding their pistols out of the water as they approach and swimming one-handed. Um, good luck with that. I'd like to see how they climbed the ship's side with their hands occupied, but instead the camera just cuts to the deck of the ship as the pirates magically jump over the gunwales.

But Frenchman's Creek avoids the common trope of The Pirates Who Don't Do Anything; i.e. pirates who never commit actual piracy because that would make them look bad. Aubrey's men do a daring combined overland-and-sea attack on a ship, kill several of the crew, and have great fun sharing out the booty. This is justified as a kind of reverse piracy; the ship they are attacking is actually a French ship that was stolen by English corsairs, and is being returned at least to its rightful nation, if not its rightful owners.

Bartholomew Roberts's articles imply that music was common aboard pirate ships, saying that musicians were allowed a rest only on Sundays. Frenchman's Creek is one of the few movies to show pirate musicians at work; Aubrey's men work to lute music all the time. But the drums and hautboys (oboes) that were reported by actual pirate attack victims are not seen.

As usual, we get full-rigged ships instead of schooners and sloops for the pirates to sail. Captain Aubrey's La Mouette is painted white and is so spotlessly clean that it's hard to believe it's ever actually been to sea. But La Mouette has no wheel; her rudder is controlled by a genuine whipstaff, a real period touch I've never seen in any other pirate movie. In Pirates of the Caribbean, Jack Sparrow famously tells Elizabeth that "what a ship is, what the Black Pearl really is, is freedom." That is what La Mouette is too, for Dona, and that's why pirate ships never grow dull no matter how many times they appear on the screen.Joan Fontaine as Dona St.

Columb dominates the set.Arturo de Cordova

as Captain Aubrey lights up

his pipe, but not the screen.Dona St. Columb

confronts Rockingham.Nigel Bruce as Godolphin.

Yes, he's an idiot.Dona and Aubrey at the whipstaff.

No sexual undertones here, Mr. Hayes, nosirree. -

I know of three basic ways ships carried boats.

1. On davits, basically timbers or metal beams shaped like upside down versions of the letter "J," with the boats hanging over the ocean from the short end of the "J." I think I read somewhere that davits didn't come along until the 19th century. Is that right?

2. On the open deck, upside down to keep rainwater out of them. This has to take up a huge amount of deck space.

3. Towed astern. This is actually shown in many of the pictures in the Osprey books on pirates. This has the obvious advantage of keeping the boats out of the way, and saves the time spent launching them, but I shudder to think of what would happen to them in heavy weather: getting swamped, running into each other, being thrown into the ship's stern by high swells, tow lines parting, etc.

So which of these methods were used when, and by which vessels?

What was the deepest water you could practically anchor in?

in Captain Twill

Posted

Thanks!

I found a book on line by Jan Glete called Swedish Naval Administration, p. 455, which says that large Swedish warships generally had anchor cables 100 to 140 fathoms long, with smaller warships having proportionately shorter cables. This matches well with an example from the Ship Model Laboratory, which mentions a 120-fathom cable on Nelson's Victory. So it sounds like a typical large warship would have difficulty anchoring in more than about 40 fathoms of water, or maybe up to 47 for an exceptionally long cable.

There's another ship-modeling post that says that, until the 19th century, most anchors had straight arms, not the gentle curve we're familiar with today!