-

Posts

652 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Everything posted by Daniel

-

CAPTAIN BLOOD (1935) Directed by Michael Curtiz. Featuring: Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, Basil Rathbone, Lionel Atwill, Ross Alexander, Guy Kibbee, Henry Stephenson, Forrester Harvey, Pedro de Cordoba, George Hassell, Leonard Mudie. Daniel’s rating: 3 ½ out of 5. Synopsis: Irish doctor Peter Blood is happily indifferent to Monmouth’s rebellion against King James II, but he readily answers the call to treat a wounded rebel, and for this he is sentenced to slavery in Jamaica. Arabella Bishop, a rich planter’s daughter, first buys Blood to save him from death in the sulfur mines, and then arranges a soft job for him as doctor to Jamaica’s gouty, gormless governor. Blood, though, is not content with personal comfort. He means to escape and turn pirate in revenge against the King. But he may not be able to have both Arabella and his vengeance. Evaluation: Five of Rafael Sabatini’s pirate novels were adapted into major movies. They were The Sea Hawk, The Black Swan, and a trio of tales that started life as a series of short stories about an Irish physician turned buccaneer: Captain Blood: His Odyssey, Captain Blood Returns and The Fortunes of Captain Blood. In all these works, Sabatini showed a flair for writing magnificent heroes, larger than life in their courage, intelligence, and strength, but with flaws as big as their virtues. The movie Captain Blood is a simple story – much simpler than the novel, much of which was cut. It’s one man’s triumph over adversity all the way, as one might expect for a Depression-era movie. A simple story is probably harder to make well than a more complex one, because there’s less novelty to sustain the viewer’s interest, and thus Michael Curtiz deserves all credit for keeping Captain Blood a riveting watch all the way through, even during the long second act on Jamaica. Blood is a great character; not just deadly and determined with a sword, but a clever planner, a wise and compassionate leader, and brilliant in his reading of men (though not of women, to his regret). Above all, he’s stubborn, refusing ever to accept the bad hand life has dealt him or stop fighting against it. There are some forces you can’t destroy, like King James or the Depression, but you can still outlast them, and that’s just what Blood does. At the same time, Blood has big flaws in the true Sabatini style, although the grand hubris he had in the novel is softened here into something more like naivete. Blood blithely assumes that he won’t get in trouble for dressing a rebel’s injuries because “Christian men don’t make war on the wounded.” Even when a royal officer threatens to hang him, Blood is so overconfident that he mouths back to the officer. And when he’s drunk, he can make serious errors in judgment, as he himself recognizes. The main reason Blood is determined to save his fellow prisoners, not just himself, is his sense of guilt toward them: they had fought against King James’s tyranny back when he, Blood, had been ignoring it. Blood’s lady love, Arabella Bishop, is well drawn too. Though no more experienced than Flynn, Olivia de Havilland is much more confident and convincing in her role. She’s independent of her bullying uncle Bishop, and fascinated but not at all intimidated by the beautiful Peter Blood. She saves his life on multiple occasions, is attracted rather than by offended by his refusal to flatter her, and finally comes to understand his resentment of being bought by her when he turns the tables on her. The worst problem with Sabatini’s novel is that none of its villains equals Blood in stature, probably because each of the short stories the novel grew from had to offer its own little bad guy for Blood to beat. The movie doesn’t completely overcome this problem – Mr. Bishop is a contemptible adversary for Blood – but Basil Rathbone’s Captain Levasseur is another story. Handsome, dangerous, and ruthless, Levasseur admires Blood at first for his success, but then fatally underestimates him. His duel scene with Blood is the highlight of the film; Levasseur takes a mad joy in sword-fighting and is certain that, having been outwitted once by Blood, he now has his opponent where he wants him. We can almost envy Levasseur when he dies doing what he loves most. What about drawbacks? Well, strange to say, the worst problem with the movie is Flynn himself. Captain Blood made Flynn a star, but it’s safe to say that it was his Adonis-like beauty that did it, not his acting. He does reasonably well in the early scenes, but every now and again a weird, forced grin crosses his face. Then, in the later scenes, when he is called on to inspire his men, his every word becomes forced, a problem aggravated by the clunky dialogue (much of it not Sabatini’s). Flynn soon outgrew this – his rabble-rousing scenes in The Sea Hawk and The Adventures of Robin Hood showed boundless charisma – but he was clearly still cutting his leading-man teeth in Captain Blood. Also, Curtiz’s comedy is often too broad, especially in the closing scene, as well as with the odious comic relief of Forrester Harvey’s Nuttall and the brainless Governor Steede. There is a very strong supporting cast egging the leads on, notably Guy Kibbee as Blood’s graceless but honest gunner Hagthorpe, and a deliciously evil Leonard Mudie as Judge Jeffreys, the man behind the Bloody Assizes that killed and enslaved hundreds of Monmouth’s followers. Sabatini will never cast as long a shadow on pirate literature as Stevenson or Barrie have, but he did something neither of those two more famous writers did: he introduced us to the pirate as a hero, not a villain. Without that idea, Flynn wouldn’t have become a star. Nor, very likely, would Fairbanks. Piratical tropes and comments: Captain Blood begins in 1685 and ends in 1688, the exact duration of King James II’s reign. The movie has a mixed record on historical accuracy. It has some magnificently rendered ship models, most especially the Spanish ship that Flynn and his men capture to start their pirate careers, but many of these were built for Napoleonic-era movies, and have square-rigged mizzen sails instead of lateen mizzens. The cannon are accurately shown being fired with linstocks. Captain Blood follows a common trope for early pirate movies: thick slashing cutlasses for the men, but elegant dueling swords for the heroic captain. In this case, Flynn and Levasseur fight with smallswords. The fencing style, though, is more suited to early rapier cut-and-thrust technique, which is much more cinematic than the extremely linear, speedy, thrusting-only tactics that would have been used with the smallswords. We also see one of the very few moments in film where pirates wear armor. Blood’s men use Spanish morions and cuirasses, which is partly justified because they’ve ambushed Spanish troops and taken their gear, but which are still anachronisms because by 1687 the Spanish hadn’t used morions for decades. A great deal of attention is paid to Blood’s articles, which are glossed over in the original novel. They are closely modeled on Henry Morgan’s articles, even specifying the same number of pieces of eight that Morgan offered for each wound, although the option of taking your compensation in slaves is mercifully omitted. We get to see a division of treasure according to these articles, with the extra shares for the maimed; in some dubious comedy, one pirate purposely shoots off his own toe to get the extra money. Blood’s Jolly Roger is unique: a white banner with a skull above interlocked arms, both wielding swords. The white color and the implication of brotherhood in the crossed arms are perhaps inspired by the mythical Captain Misson’s flag. Unfortunately, the buccaneers hoist it only once for practice, and after that it serves for a few seconds as a transparent overlay for a montage of implied derring-do. We never see it again. Port Royal is represented with Spanish-style adobe walls, square towers and tile roofs, appropriately enough for a former Spanish colony. But it has been provided with sulfur mines to threaten Blood with; Jamaica actually had no mining industry until the 20th century. Bishop is a sugar planter, which we would expect. His slaves are shown working a gigantic machine whose purpose is not apparent: it has a giant horizontal wheel for the slaves to turn, and a giant vertical wheel which is water-powered, linked by a second vertical wheel which doesn’t seem to do anything at all. Levasseur’s wardrobe is a perfect Halloween pirate costume; puffy-sleeved linen shirt, sash belt, bandolier belt, and tight trousers with high boots. Other clothing is surprisingly restrained, with Blood often appearing a simple waistcoat. The most luxuriously dressed characters are the Bishops, uncle and niece both. Broad-brimmed 17th century plumed hats are common. Periwigs do appear on Governor Steede and Judge Jeffrys, but not on others who you’d expect, like Mr. Bishop. Sabatini has Blood himself wearing a periwig at his trial, but Curtiz doesn’t, appreciating that modern audiences won’t cheer for a fop. Peter Blood, M.D., sometimes forgets the Hippocratic Oath. Arabella Bishop can buy me for ten pounds any time she wants. No, Bud Light! Basil Rathbone really sinks his teeth into the role of Levasseur. Blood's Jolly Roger. I want one, I want one! Leonard Mudie's Judge Jeffrys and his Periwig of Evil. This is exactly why we don't give slaves armor. Or swords.

- 34 replies

-

- movies

- pirate art

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

From the album: Captain Blood

-

From the album: Captain Blood

-

From the album: Captain Blood

-

From the album: Captain Blood

-

It has that little hook on the top of the quillion, which I've seen on many historical cutlasses. I always wondered, is that supposed to stop the enemy's blade from slipping past the quillion and cutting you?

-

Daniel DeFoe used the phrase "swing by the string" for hanging; a Newgate girl sang, "If I swing by the string, I shall hear the bell ring, and then there's an end to poor Jenny." Jonathon Green's Crooked Talk has the phrase, "dance at the sheriff's ball and loll out one's tongue at the company," "dance at Beilby's ball, where the sheriff pays the fiddlers" or "where the sheriff plays the music." One could also "shake" or "shiver one's trotters at Beilby's ball." The typical 18th century gallows is shown with two posts connected by a single crossbeam. Usually the condemned man or men (often several were hanged at once) would be brought to the gallows in a cart, facing backward. Their hands were tied in front of them so they could pray. A noose was placed over the neck, and then the cart would be pulled away, leaving them to die slowly from strangulation and pressure on the carotid arteries. Family members might pull on the victim's feet to hasten death. The victim's clothes and corpses belonged to the hangman, and the family had to buy the dead man's corpse if they wanted to bury it. Am 18th century French hanging was more complex. The condemned was carried in a cart to the gallows, with three nooses tied around his neck. Both the hangman and the condemned climbed a ladder, and the hangman tied two of the nooses to the beam. Then the hangman would throw the victim off the ladder with a push of his knee and a pull on the third noose, and would hasten the strangulation by hanging onto the beam with his hands and pushing on the tied hands of the victim with his feet. (Compared to the English executioners, those French guys really earned their pay). In the 17th century, English hangings tended to be with ladders, with the hangman simply twisting the ladder out from under the victim's feet. Platforms with trap doors were not common until the 19th century, but there was one in Boston as early as 1694, and seven of Quelch's pirates were hanged on it.

-

I'm not sure I understand what you mean by "'off' expressions." Do you mean slang phrases, like "being turned off," "dancing the hempen jig," or "to walk up Ladder Lane and down Hemp Street?" And then you also want to know about period methods of hanging?

-

Wow. Very interesting. Oddly, Wikipedia's Jolly Roger page used to include a theory that Woodes Rogers's name birthed the flag's name. But there was no supporting reference, and I zapped it after it had hung around unsupported for a couple of years. If I could verify that Weekly Packet reference, I would put it back in. Is the Weekly Packet published in a bound volume somewhere? Or in an archive?

-

That's neat; I listen to a lot of books on tape in my car, and I too find that the reader makes a big difference. For me, one of the worst things about Dana's Two Years Before the Mast was Bernard Mayse's reading of it; plodding, raspy, and mispronouncing the Spanish and sailing words. On the other hand, I'm listening now to Cormac McCarthy's No Country For Old Men, and I am loving Tom Stechschulte's performance of it. He does the Texas accents perfectly, without making them all sound the same, and he has a great feel for the narrative; he picks up the pace in the action scenes, then slows down and savors the words in the reflective scenes. He really performs the book better than McCarthy wrote it (what the heck is up with all those "ands" McCarthy uses? Commas were invented for a reason).

-

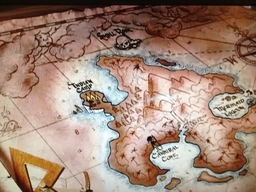

PETER PAN (1953) Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Jack Kinney. Featuring the voices of: Bobby Driscoll, Kathryn Beaumont, Hans Conried, Bill Thompson, Paul Collins, Tommy Luske, Candy Candido, Tom Conway, Heather Angel. Daniel's rating: 3 out of 5. Synopsis: It’s Wendy Darling’s last night in the nursery with her brothers John and Michael, before her father sends her to live alone in a room of her own. On this last night Peter Pan come to the nursery to take the three children flying away to Neverland, where children never grow up, but where they do need a mother like Wendy. The only grownups in Neverland are a crew of wicked pirates led by Captain Hook and his bumbling bosun Smee, who are always searching futilely for Peter Pan and his never-grown-up Lost Boys. But Peter Pan’s pixie companion Tinkerbell is very jealous of Wendy, and that may prove Peter Pan’s undoing . Evaluation: Peter Pan and Treasure Island are the two most popular pirate stories ever written in English, and they are as different as Ashley Olsen and Clint Eastwood. Treasure Island is a very masculine story, full of danger, violence, and virtue battling depravity, driven by Jim Hawkins’s search for gold, for manhood, and the lost father that he naively believes he has found again in Long John Silver. Peter Pan is a feminine, childlike fantasy, just as much about Wendy Darling as it is about Peter Pan (J.M. Barrie’s novel was titled Peter and Wendy), and is about the magic of being a child and having the childish imagination. Treasure Island is about Jim Hawkins growing up; Peter Pan is about Wendy Darling staying a child, at least for a while longer, while Mr. Darling regains a little of the child he once was. Peter Pan, the boy who wouldn't grow up, is carefree and contemptuous of danger, seemingly unaware of his own mortality. He is interested in Wendy because she tells stories about him, which he tells to the Lost Boys, and when he invites her to Neverland, he wants her to be a mother there. All the girls in the story, though, want to be Peter's romance, not his mom, - Wendy, Tiger Lily, the mermaids, and most especially Tinkerbell - and the bizarre thing is that he never notices this. Even when Tinkerbell tries to murder Wendy, Peter never figures out that this is jealousy at work; all he understands is that Tinkerbell has betrayed the gang, and so he banishes her. Ironically, Peter is voiced by Bobby Driscoll, the same child star who played Jim Hawkins in the 1950 Treasure Island, who would die tragically from the effects of drugs and alcohol before the age of 40, an end more reminiscent of Captain Flint than Jim Hawkins or Peter Pan. Wendy is just on the cusp of growing up; she is already half a mother to her younger brothers, and clearly her being sent out of the nursery will mean the end of her childhood. And she already has grown-up attitudes and prejudices; she is jealous of Peter, demands that they can't stay in Neverland like "savages," and is quite ready to drown rather than become a pirate. The villain, Captain James Hook, is really the most remarkable character in the story. He is the only grown-up of the three leads. And what is it that marks him as a grown-up? The sound he always hears: tick-tock, tick-tock. Time is running out. Death is nearing. With this tortured soul as his main example of adulthood, no wonder Peter Pan doesn't want to grow up. From the moment we meet Hook, he is hunting Peter, who cut his hand off in a fight long ago. But why was Captain Hook fighting Peter in the first place? My best guess is plain envy. He can't stand having someone else around who do plainly doesn't suffer the constant terror of death. But Peter Pan, for all that it says to grown-ups, or just reveals about them, is really meant for children. It wasn't a random whim when Barrie willed the rights to Peter Pan to a children's hospital charity; he imagined this story cheering children who were sick, some perhaps dying. How good is Peter Pan for them? Well, when I was a kid I loved it; now that I’m grown, my own son loves it; and I think most children will too. Being a child means having the Unknown much closer around you, always at arm's reach, sometimes close enough to bite. That’s not just because you haven't had all your schooling yet, but because you haven't had time yet to recognize patterns that adults see instantly. You don't know yet that the mad killer under the bed is a phantom while the drunk driver is an omnipresent threat; you don’t know yet that buried treasure and an M.D. degree aren’t equally plausible paths to wealth. The constant presence of the Unknown gives children a capacity for fear and wonder that shrinks or dies as we grow up. Children's feelings about a story depend on what you put in that so-huge, so-close Unknown. So when you tell them that the Unknown beyond the second star to the right contains not the monster under the bed, but Indians and mermaids, hollow trees and pirates, and Captain Hook can be avoided because there you can FLY, you will get that squeal of delight that only children can make. Piratical tropes and comments: Peter Pan is one of the least credible pirate movies ever made, because Hook's pirates don't seem to be interested in stealing anything. There aren't even any other ships to attack or towns to plunder. Maybe this is why the pirates seem to be perpetually mad at Smee when he serves them their thin victuals. Barrie wrote that Hook looked like "the ill-fated Stuarts," and he certainly could pass for Charles II in this movie with his long wig and coat, sinister mustache, narrow face, and stockings. His shoes are bizarre, with something like wings protruding from the ankle; whether this is a Disney invention or some short-lived period fashion I can't imagine. He acts like an absolute monarch, too, abusing his confederate Smee and shooting one of his own men out of the rigging for singing annoying songs. Hook's hook is a trope in itself, of course. Obviously, he’s named after his prosthesis; Barrie wrote that revealing Hook’s true name would have scandalized the country. This is the story that made the hook a fixture in pirate mythology. Some real pirates lost a hand, for sure – Christopher Condent was nicknamed “Billy One-Hand” – but there’s no proof that any used hooks. Hook's sword is a complete anachronism; a. 19th century épée de duel with cup guard. The other pirates stick to short cutlasses that are perhaps a bit wider and straighter in the blade than typical pirate cutlasses, but would certainly serve for hacking and stabbing on a crowded deck. One last accessory that the movie’s Hook retains from Barrie is a double cigar holder. Unlike most of Barrie’s pirate images, this one never caught on; I’ve never seen a cigar holder in any subsequent pirate movie, much less a double one. I severely doubt this is period; cigars weren’t popular yet in the 18th century. The period paintings show pipes and snuff boxes, not cigar holders. Probably the most important trope that Peter Pan popularized is walking the plank, done here face forward (not sidewise as in Pyle’s picture), and with the hands tied, but no blindfold, although Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. had already walked the narrow timber road in The Black Pirate. There are two cases from the 19th century where pirates did this, and one from the 1750s when mutineers used the plank, but there are no known cases from the Golden Age. Smee and the other pirates are very different from Hook, ragged and ugly and brutal. Smee where’s the usual backward-bending sailor’s cap bends backward, and he wears sandals, one of the very few screen pirates to do so. The other pirates tend to go for the headkerchief style popularized by Howard Pyle. Peter Pan follows the Black Pirate in having the pirates’ victims all tied to the mast as they await their fate. At least one 19th century pirate victim was reported being tied to the mast and tortured, and Captain Low once burnt a ship with the cook tied to the mainmast, but tying bunches of people to the mast at once probably wasn’t practical. Lastly, this is the only pirate movie I can recall where the pirates try to force prisoners to sign the articles under threat of death. Refusal means the plank. I can’t imagine why this hasn’t been used more often. Real pirates did this all the time, notably Roberts and Low. And it has such dramatic potential, as we see when Wendy refuses and faces her death on the plank so bravely. I want to see more movies, and more stories, that deal with this. Peter Pan brings a knife to a swordfight; luckily, that's all he needs Every pirate map should have an Indian Camp, a Cannibal Cove, a Mermaid Lagoon, and a Skull Rock. All this female attention can't be good for Peter. Tinkerbell, have you been up to no good again? Hook, meet Crocodile. Crocodile, meet . . . oh. You already know each other. Words couldn't possibly improve this picture. "How're we doing?" "Same as always." "That bad, eh?" Greg Louganis never had to do this with his hands tied.

- 34 replies

-

- movies

- pirate art

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

He grew a new head after he swam around Maynard's sloop three times. Blackbeard is hard-core.