-

Posts

2,579 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Everything posted by Fox

-

I didn't say that yellow was the only colour used before 1718...

-

If you insist I'll root out the original quote (though I've posted it on here before so it should be findable with a search). The original quote certainly suggests that Shelvocke/Betagh believed yellow to be the commonest colour for pirate flags in 1718. If you have any evidence to the contrary I'd be pleased to see it.

-

Part of the description of Sierra Leone inserted in the chapter on Davis was later used by John Atkins, surgeon of the Swallow, in his own book. Since Atkins had actually been there and Johnson (as far as we know) had not, the obvious conclusion is that Atkins wrote the description and gave it to Johnson, then reused it in his own book years later. The account of the trial of Roberts' men in the GHP is also taken from the record of the trial kept by Atkins in his capacity as register (a kind of clerk) of the court. Johnson may have got it direct from Atkins, or he may have copied from the printed version, which in turn came from Atkins' record. Although Roberts was reputed to have executed the governor of Martinique, and the rumour was repeated by Johnson, there is no evidence that he actually did so. There's nothing mystical about Johnson Those six or seven men may have actually been: "Thomas Lamburn, whose father and mother live in Robin Hood's Alley in Suffolk Street in the Mint James Bradshaw, living at the Cork, a public house in Cork Lane in Spittlefields and keeps the said house John Cherry, lodging at the White Lion, a public house in Wheeler Street, Spittlefields Thomas Jenkins (whose real name is Francis Channock) to be heard of at the Sign of the Golden Bull or Yorkshire Gray a little about the wet dock in Rotherhithe. Charles Radford, a lodger at Mr Hitchcock's, a musician, near the Watch house in Brook Street in Ratcliffe Thomas Haydon, gone to sea but when at home lodges at Mrs Price's in Elephant Lane Rotherhithe" Of these men, only James Bradshaw appears to have actually been taken up for questioning and committed to the Marshalsea prison, but he claimed to have been forced by Howell Davis and was not brought to trial. The man who accompanied Kennedy was probably "William Callifax, at Dublin near Cable Street". There is some evidence to suggest that at some point Callifax was actually in command of the company.

-

Oh yes, by the early 1720s black was so common a colour that the phrase "black flag" was synonymous with a pirate flag. In 1718 however privateer George Shelvocke wanted to appear intimidating from a distance and so hoisted the colours of the Holy Roman Empire, a black eagle on a yellow field. The reason for doing so, and I'm paraphrasing the original account by one of his officers named William Betagh, was that it was the closest thing they had to a pirate flag, since pirate flags were yellow with a black skeleton. At that date, a yellow flag was not associated with quarantine.

-

It's quite possible, I don't see any reason why not, but bear two things in mind: Firstly, although a nucleus of Roberts' men had been together since Davis led the mutiny on the Buck, many of Davis' men had left the company by the time of the final battle: John Taylor had joined Cocklyn's crew, and it's possible some of his friends and supporters went with him; Kennedy had sailed for home with a sizeable number of men; and Thomas Anstis and a good number of the company deserted and went on their own account. By the time of the last battle, probably the majority of the company had not been with Davis. Secondly, Roberts' company took a lot of ships between Snelgrave's vessel and their last battle, so the watches and waistcoats could easily have come from somewhere else.

-

Oh, if you want modern fabrics then the best thing I can recommend is a black cotton bedsheet

-

One pirate's flag (Harris' I think, but I might be mistaken since I'm too lazy to check) was decribed as black by one witness and blue by another. I think this is probably down to the dye. True black was very hard to dye and very expensive, but a lot of cheaper very dark colours might be described as black. In the case of the flag I think one witness described what they were supposed to see - a black flag - while the other described what they actually saw - a blue flag. Also, bear in mind that not all pirate flags were black: red was common, there's more than one ref. to a white pirate flag, and there is evidence to suggest that until 1718 at least the most common colour for pirate flags was yellow. The ras de St. Maur reference isn't from Johnson, so you won't find it even in the best editions... And no, I don't think pirates dyed their own black. For what it's worth, in the only period account I can think of describing the application of a design on a pirate flag it was painted.

-

Hmm, some interesting points... First off, the only actual account I can recall offhand of pirates holding a mast sale is that posted above, but it included more than just the coats - at least Snelgrave's watch was also sold. However, I suspect that it was more common than the one source suggests, simply because it makes a lot of sense. Given that many items taken by pirates would be impossible to divide equally, the mast-sale would be a good way of realising the value of the items and levelling the shares received by each pirate at the same time. Methods of distributing loot varied from ship to ship, as one would imagine. John Taylor's company apparently kept a common chest and divvied up the loot whenever they made landfall. Kidd's men had a more formal division wherein each man was called in turn and swept his share up into his hat. Anstis' crew appear to have divided loot after each ship they captured. The keeping of a common fund, even by companies divided over more than one ship, was fairly commonplace. When Charles Harris' ship was captured the authorities found no money on board because all the loot was kept on Low's flagship. Bellamy's company also kept a chest, but did not formally divide the loot. Instead, each man could have money whenever he wanted it by applying to the quartermaster, who kept an account book of everything given out. Were pirates savers? Well, why not... many of them certainly experienced a "short life and a merry one", but that doesn't mean that they were hoping for it. Roberts' articles, for example, state that no man was to talk of breaking up the company until each had received £1,000. Retirement from piracy was certainly the eventual aim of many (perhaps most) pirates, and they naturally hoped to have accumulated enough to do so in style. (Cue the argument about pirates' motives...)

-

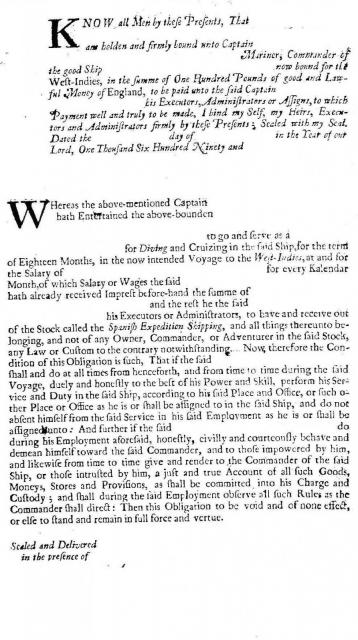

This was the standard contract which everyone on the expedition had to sign, from Captain to cabin boy, and one of the objectives of the expedition was to dive Spanish treasure wrecks. The best known of the people who signed this particular contract was Henry Every... And it's thanks to Henry Every that this example of a contract has survived. The cash bond was not an essential feature of such contracts, perhaps not even that common.

-

Wool bunting was probably not the be-all-and-end-all flag material, and to be honest I wonder if it's something of a reenactorism. Some years ago Gentleman of Fortune did some research into period flags in a general sense and pronounced wool bunting to be the most common material. GoF's research is usually pretty good, but I don't personally know what his evidence was in this case. Regardless, since then whenever flags get mentioned, so does wool bunting. Aside from the aforementioned dirty tarpaulin, the only two materials I've seen period references to for pirate flags are 'ras de St. Maur', which is a woollen cloth, or silk. Linen would work and is a period-available cloth, so if you can get cheap black linen then go for it.

-

Yep, that's what happens in Twill! While the silk stocking is (I believe) the only complete piece of clothing found so far, there are over 100 other pieces of fabric of different types. The silk stocking is especially interesting because there's a very high chance that the original owner can be identified - John King, a fairly wealthy lad, whose ownership of silk stockings is not surprising. This also raises the issue of his shoe. The much vaunted "Whydah shoe" has been copied extensively for pirate reenactors, but given its origins I have long questioned how far it should be assumed "typical" Buttons and buckles occur frequently in sailors' wills and seem to have been a form of portable wealth. Define successful. The capture of the Whydah aside, Bellamy and his company were no more successful than many other pirates like Blackbeard and Roberts for example. There is a tendency to assume that most pirates were not so successful as the "big names", but in practice the companies of Bellamy, Roberts, Blackbeard, Taylor, La Buse, Low, and other "successful" pirates made up a very considerable portion of the pirates active in the GAoP. One thing to bear in mind with any artefact assemblage like the Whydah stuff is that it is, at best, partial, and can only tell us what pirates had - not what they did not have, or how prevalent any particular item was. For example, only half a dozen or so plates have been recovered, but there were over 140 men aboard when she sank, so either we have to accept that ~135 plates have been lost (or not yet found) or that only 4% of pirates had plates...

-

For some reason I can't find the original jpeg of this, but here's a 'blank' contract (by which I mean I've removed all the hand-written stuff) signed by each member of the Spanish Expedition of 1694.

-

In the case of the document above, it's an individual contract so it's got the signature of the person signing on, the owner of the expedition, and one or two witnesses. There is a set of pirate articles in JF. Jameson's Privateering and Piracy which has a mix of signatures and marks, and both Marcus Rediker's Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, and Peter Earle's Sailors have analyses based on the number of signatures and marks in the papers of the High Court of Admiralty. Roughly, it's about 2/3 of sailors and virtually every officer. However, as noted elsewhere, all that shows us is how many people could sign their name, nothing more.

-

The ship's articles are listed in Rogers' book (the re-written set, that is, not the original set), but not the individual contracts.

-

I can do you a 1694 privateering crew contract if that's any use?

-

It's odd, in some cases the articles appear to have been adhered to with an almost devotional fervour, but in other cases "more like guidelines" would appear the most appropriate description. For further examples from Roberts' articles, at least one boy was definitely aboard Roberts' ship, despite being banned in the articles; soldiers who joined Roberts' company were only awarded 1/4 of a share, instead of the whole share they were entitled to; and, despite Roberts' articles being the only set to stipulate that "every man shall have a vote...", in practice less than half the people on board were enfranchised.

-

It is surprising just how much paperwork pirates did keep. As well as the obvious articles, log books would probably have been kept by any trans-oceanic pirates because they serve a navigational purpose, they're not just about reporting to one's superiors. We also know that at least Sam Bellamy and Ned Low's ships were run by 'watch bills', which in the usual run of things detailed who was in which watch and often what their duties were. This too makes perfect sense because it enabled commanders (pirate or otherwise) to ensure that the members of the crew were put to the best use. As far as keeping a record of captured ships, again, we know that on Bellamy's ship at least, the quartermaster kept an account book. As for literacy, that's a thorny issue made more difficult by the fact that 'literacy' itself is a 19th century construct. In the 17th and 18th centuries reading and writing were seperate and distinct skills, though obviously linked by the written word. Many people could read but not write, many people could write their own name but nothing else, some people could write their own name but not even read. About 2/3 of lower-deck seamen could write their own name, and virtually all officers could, but that only actually tells us how many people could write their name, nothing more. What we can say is that anyone who wanted to progress even as high as boatswain would have need to be able to read and write in the course of their professional undertakings, and that everyone in England and the English colonies had at least theoretical access to free schooling. Not everybody went to school of course, but there's no way of enumerating how many children were educated in the home. At school, reading was taught first, followed by writing, and finally by numeracy - they weren't taught side by side as they are now - so anyone who had had even the most basic schooling would be able to read to some extent, even if they couldn't write a word.

-

I've never come across a period reference to the Nassau widow I'm afraid, or even any other modern reference. Emmanuel Wynne's flag was described by a Royal Navy officer, I forget who described England's, but I think it was one of the officers of the East India Company ship Cassandra. Other pirates known to have flown the skull and cross bones or a simple variant include Blackbeard, Thomas Cocklyn and others

-

Thanks for resurrecting this thread Mission - Articles are my current favourite topic! In answer to your question, I suspect that that article is more to do with sociabilty than fire risk. Candles are no more dangerous on a wooden ship after 8pm than before, though I suppose that a candle in the hands of a drunken man is more dangerous than in the hands of a sober man, and that men are more likely to be drunk after 8. I'm not convinced that it was just Roberts who wanted a bit of peace and quiet below decks after eight. The idea of all-night drinking binges was not so widespread in the GAoP, and people did tend to go to bed earlier. Evidence from, I think, George Roberts' account bears out that this applied to pirates as well. Even when pirates did indulge in all night drinking, they wouldn't have wanted to do it every night, and probably not everyone would have wanted to join in. Such forms of social control for the preservation of the community harmony were one of the most important aspects of the articles. I'm reminded of the articles employed by American PoWs in the Revolution and War of 1812, which served exactly the same purpose and contained many similar clauses to pirate articles. One set, I forget when and where except that it was on a hulk rather than a prison camp, included a rule about not smoking below decks, and the memorialist who mentions it (Benjamin Palmer?) links it specifically to the comfort of the sick, not fear of fire. The interesting thing is that, in that case at least, it was scrupulously obeyed. The author bemoaned the fact that when the prisoners were confined below decks at night he went nearly mad with craving but even though his hammock was next to an open gun-port he still wouldn't smoke, because it was against the rules.

-

The flag in the Daily Mail article has recently been discussed here: http://pyracy.com/index.php/topic/18467-sword-on-flag-question/ My thoughts on pirate flags could run to many many pages (see my posts in Mission's links above!), but my over-riding thought is this: taking all of the period references to pirate flags together, the most common device was easily the good ol' skull and cross bones.

-

I resemble that remark! No, Johnson's far from perfect, and I've never yet read a book on pirate history that I couldn't pick some hole in or other, including my own. Is Blackbeard's journal entry authentic? It doesn't seem right to me, but I realise what a terrible basis that is for an argument. If Blackbeard's journal had survived then it would most likely have been stored in the records office at Williamsburg VA, which suffered several fires before anyone really thought to look there for Blackbeard related stuff. Maynard doesn't mention finding a journal specifically, but he is known to have recovered several documents from the Adventure, which conceivably could have included the journal. Of course, even if Maynard did recover Blackbeard's journal it doesn't follow that Johnson really quoted from it. I will say this however, the Blackbeard journal entry is the only journal "quoted" in the GHP, and if any pirates' journal was likely to have survived it would have been Blackbeard's (because we do know that other incriminating documents were recovered from his ship). I don't believe it myself, but I'm not prepared to rule it out.

-

Can't help with pairs of standards I'm afraid, but somewhere round here there was a long thread about different "ropes" on a ship, which got up to about 20 different items called "something-rope" on a ship. Interestingly, while looking up standards in the index to Butler's dialogues, he refers to "standing rigging" as "standing ropes", so for the 1620s-1680s at least, there was a heckuva lot of "rope" on a ship. If you're putting up a tent and looking for the raw material then "rope" or "line" would be equally acceptable. FWIW, a gun is a gun on land too. It's only a cannon if it's of cannon size - the exact size of a "cannon" varies, Ward's Animadversions of War gives the name to a gun firing a 64lb shot. A 32lber is a "demi-cannon", a "culverin" fires a 17 2/7lb shot, a "saker" fires a 3 1/2lb shot, etc. - but they're all "guns" whether on land or sea. It's a bit like the confusion between a cask and a barrel. Guns actually does seem to be one of those areas where terminology was important to contemporary observers: lots of sources talk about "guns", but if they use a more technical term then it's generally referring to a particular size of gun - I've never run across a "swivel-cannon" in a period source for example, because 64lbers were never mounted on swivels.

-

No reason not to believe the Evans letter. The stuff in the appendix is usually pretty good, and there's no reason to think that the letter isn't genuine. Sodomy and the Pirate Tradition isn't worthless (even the worst books can be used to prop up wobbly tables), but it does start off with a fairly major agenda, which it supports by inaccurate premises (pirate ships were a bit like prisons, and we know that situational homosexuality occurs in prison therefore it must have done on pirate ships too - trouble is, pirate ships were not much like prisons) and a spectacular lack of evidence (the only actual evidence of pirate homosexuality Burg produced was a false accusation made against a buccaneer).

-

The story of the quilted up coins comes from the Examination of John Dann, 3 August 1696, in the Board of Trades and Plantations papers at the National Archives, Kew, and reprinted in John Franklin Jameson's Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period. "This informant went to Rochester on Thursday last and was seized there the next morning by means of a Maid, who found Gold Quilted up in his Jacker hanging with his coate, he was carryed before the Mayor, who committed him to Prison and kept his Jackett..."

-

I've had a quick scan through that book. It doesn't look bad, but I picked up a few debateable points in the few pages I really read properly. My biggest concern with it is that, like so many books of its kind, it uses the pirate label to cover research which is predominantly about buccaneers. Looking through the primary sources in the bibliography, I see Atkins, Ashton, and Johnson, and a mass of stuff about buccaneers. He didn't even, apparently, use Snelgrave's book, which is filled with juicy details of daily life and is readily available, let alone take the time to find and translate du Buquoy's account, which is hard to locate and in French, but contains as many good details as Snelgrave. Lesser known pirate-captive accounts are also ignored. There is no sign of any archival research, which means a massive body of evidence that would have provided some really interesting material has been overlooked. And I don't like his definition of "Jolly Roger" in the glossary. I can forgive him connecting it with "jolie rouge", but he says it's a Victorian term when it appears in numerous sources from 1719 onwards.